Welcome to TV Formatting Fundamentals! In this blog series, we explore the on-page structure of different types of TV series.

In earlier posts we’ve looked at multi-cam sitcoms, episodic dramas and single-cam sitcoms. All previous posts have explored scripts with clearly delineated commercial/act breaks—meaning they’re scripts that tell you where each new act starts and stops.

This week we’re charting new territory and diving into serialized dramas, the kind you find on streaming services and the upper channels of your cable subscription.

Serialized dramas include Game of Thrones, The Handmaid’s Tale, Pose, The Wire, Breaking Bad…. Unlike episodic drama, serialized drama tends to treat each episode like a chapter in a book. Episodes might have some self-contained elements, but for the most part, they’re pieces or fragments of a much bigger season and series narrative. A standard episode of serialized drama typically includes four acts or four acts and a teaser.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, HBO shows like Oz, The Sopranos, etc. didn’t include act breaks in their scripts. The episodes weren’t airing with commercial interruption, so there was no need for them. As a result, these shows have a more cinematic feel.

These days, it’s rare to find serialized drama scripts that actually include act breaks on the page. It’s particularly rare amongst shows that drop/air on streaming platforms.

Neophyte TV writers might assume that because a script doesn’t explicitly note its act breaks on the page that a script does not contain act breaks.

Such an assumption is easy to make. Even some of our earlier blog posts about spec script formatting are somewhat perplexing on this matter. If a script doesn’t delineate its act breaks, we say it doesn’t have any.

But almost every TV show is broken into acts, even if those acts are not spelled out on the page.

Good stories have turning points, mysteries, and revelations in order to keep a spectator interested. Just because a writer doesn’t flat out state that this is the end of act one doesn’t mean the end of act one isn’t there. Feature screenplays are often broken into acts, but the writer doesn’t announce “END OF ACT ONE” on the page.

So, with this blog post, we’ll do a little something different. We’ll offer instruction on how to spot the act breaks in cable/streaming scripts that don’t explicitly show them.

We’ll stop looking at scripts without act breaks like this:

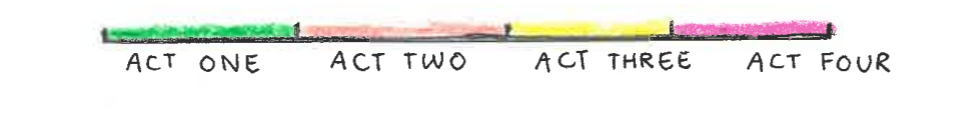

And start to see them more like this:

This knowledge will come in handy when you’re spec-ing a serialized drama show, writing a serialized drama pilot… or trying to get more efficient with outlining and drafting.

The best way to learn serialized act structure is, of course, to read scripts. It’s especially helpful to start with shows that air(ed) with commercials… shows like Pose or Breaking Bad. This way you can see specifically where the acts stop and start on the page.

As mentioned before, you’ll find that scripts of this nature often have four acts. Sometimes they include a teaser or even a fifth act, but four acts seems to be the standard.

The great serialized dramas tend to feature huge ensemble casts, but those huge ensemble casts are usually anchored by one protagonist (or sometimes a small group of them). Part of what makes a season of serialized drama feel like a movie is that we follow that one central character (or, again, a few of them) in the way that we follow one central character in a film.

In fact, the structure of one serialized drama episode can feel a bit screenplay-like in nature, especially if you’re looking at a pilot.

ACT ONE is where we meet the protagonist in their ordinary world. By the end of that act, there’s a catalyst, a big decisive action or an event that shakes things up. In the shooting draft of the Pose pilot, the first act is 16 pages long. We meet protagonist, Blanca, in New York City in the late 1980s. She walks/competes in balls for the House of Abundance. After testing positive for HIV, Blanca decides to pursue her dream. At the end of the act, she leaves House of Abundance to start her own house. This is not unlike the first act in the pilot for Breaking Bad, where Walter White lives a quiet, dull life as a chemistry teacher, but then one day collapses at the car wash.

ACT TWO finds our protagonist(s) in a new situation, pursuing something new with great agency and meeting the people that will help or hinder them in that pursuit. In Pose, Blanca meets Damon, a brilliant dancer and a runaway from Pennsylvania, who has no place else to go. By the end of the act (on page 35), Damon joins Blanca’s new house—The House of Evangelista—and his dancing talent will help them compete in the balls. In Breaking Bad, Walt officially gets diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer, but he spots a former student, Jesse, who now cooks and deals meth. He blackmails Jesse into letting him join his operation.

In a way, you might say that ACT THREE is where the protagonist makes the decision or takes on the task that will be the backbone of the entire series. Blanca decides that House of Evangelista must challenge House of Abundance. She wants a name for herself. In Breaking Bad, Walt and Jesse gather equipment and an RV and cook their first batch. Right at the end of the third act, Walt encounters some jocks making fun of his son, Walter, Jr., who has cerebral palsy. He stands up for his kid by kicking the instigating jock in the back of the leg. As the script says: “Walt feels a kind of power—one that’s completely brought on by an absence of fear.” This provides a hint of the profound character change that’s to come (and what the show will be).

ACT FOUR is the final act (but really it’s the beginning of the entire series). In Pose, in their first ball, Blanca and the House of Evangelista lose to the House of Abundance, but gain two new members in Angel and Pito. Despite losing, the house becomes more of a family and is equipped to meet future challenges head on. In Breaking Bad, after cooking starts a brush fire and the threat of sirens leave him spooked and beat, Walt possesses new vigor, energy and power in his life, which he too (with the partnership of Jesse) will bring to future challenges.

Both shows end their acts with “act outs” or cliffhangers that make a viewer want to come back after the commercial break. With this knowledge, let’s see if we can locate the act breaks in a show that does not specify them.

The general gist of The Sopranos is this: Balancing family and work life starts to take a huge toll on the mental health of New Jersey mob boss Tony Soprano. When he starts having severe panic attacks, he quietly visits a therapist.

Will it work for him? Will he find balance and well-being? Will he quell all the nagging, threatening voices around him? Is he doomed for a downfall?

The show wrestles with a lot of moral, existential questions. In the pilot, we’re introduced to Tony, his overarching problem, and the array of frustrating family members and colleagues around him. The script is subtly broken into a teaser and four acts—all structured around Tony’s panic attacks.

TEASER